On paper, the apartment at 540 Concord Ave. in the Bronx was a good fit for Ingrid Rivas’ growing family. It was close to the subway, a few blocks from a park, conveniently near shops and diagonally opposite the local public school. And the landlord, unlike some in New York City, accepted tenants with housing vouchers.

But the Rivas’ living situation deteriorated quickly after the family moved in, in 2019. Within four years, medical records show her four young children had all been exposed to high levels of lead. City inspectors later found old paint crumbling off a window, doors and kitchen fixtures, according to housing department records. The eldest child, who is now 6, was also diagnosed with developmental delays, which his parents believe were exacerbated by lead exposure. Lead is a potent neurotoxin that can cause irreversible brain damage in children.

City housing records show Rivas’ children may not have been the first to be exposed to lead in the apartment. The unit had received lead paint violations over three separate years nearly a decade before her family moved in. The citations were issued under Local Law 1 of 2004, a sweeping set of regulations passed by the New York City Council that require landlords to fix dangerous lead paint conditions.

Among many other provisions, the law requires landlords to inspect young children’s homes for dangerous lead paint conditions and remove lead paint from areas that pose the greatest risk. These so-called “friction surfaces,” like the Rivas’ windows, doors and cabinets, produce dangerous lead dust that can be easily ingested by children.

The law aimed to prevent lead exposure in the first place, and by most measures it has been highly successful. The number of children poisoned by lead each year has plummeted more than 90% since Local Law 1 went into effect, city data shows. But that still leaves around 5,000 children under 6 who test positive for elevated blood lead levels each year.

Many supporters of the legislation say the law would be even more effective if then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration had not stripped out some of the original bill’s toughest provisions, including a 2007 deadline for removing lead paint from friction surfaces. Instead, lawmakers settled on a requirement that landlords remove lead paint on friction surfaces when a tenant moves out. At the time, Bloomberg was concerned about the legal and financial burden that the original suite of rules would place on property owners, said Stu Loeser, a spokesperson for the former mayor.

A Gothamist analysis of nearly 20 years of data collected under the law shows that more than one-fifth of all homes cited for lead paint have racked up repeated violations year after year — making Rivas’ apartment one of more than 12,000 in the city that may have poisoned multiple children since the rules for landlords were put in place.

Some were cited nearly every other year for lead paint hazards. More than three-quarters were cited twice during the 20-year span. Publicly available data does not show how many of these violations are linked to actual lead poisoning cases, but a child with an elevated blood lead level is one of the most common reasons that inspectors visit an apartment and issue citations. New requirements that go into effect later this year will help close loopholes created during the Bloomberg era, some public health experts said.

The city’s housing department is responsible for ensuring that landlords comply with Local Law 1. In response to Gothamist’s findings, spokesperson Natasha Kersey said in a written statement that the agency’s “No. 1 goal” is protecting tenants. She cited the city’s Emergency Repair Program, which allows the city to fix immediate lead paint hazards on the landlord’s dime if they fail to do so willingly.

Until recently, the city rarely issued violations against landlords who failed to remove lead paint where required when an apartment becomes vacant, said attorney Matthew Chachere, who helped draft much of Local Law 1. City data shows that only two were cited from 2004 to 2019. Both violations were linked to lawsuits Chachere filed on tenants’ behalf, he said. The pace of enforcement only picked up in 2021, when an amendment to the law required the city to audit landlords’ lead paint inspection records.

Many landlords also skip out on required annual inspections that are meant to catch peeling lead paint before it harms a child, and most haven’t faced any consequences, city data shows. A 2023 audit by the housing department found that, out of more than 200 randomly selected buildings, 94% didn’t have the inspection records that landlords are required to keep. Skipping those inspections is a misdemeanor, punishable by up to six months in prison, but the audit shows that only a small proportion of landlords have had to answer for the neglect in court.

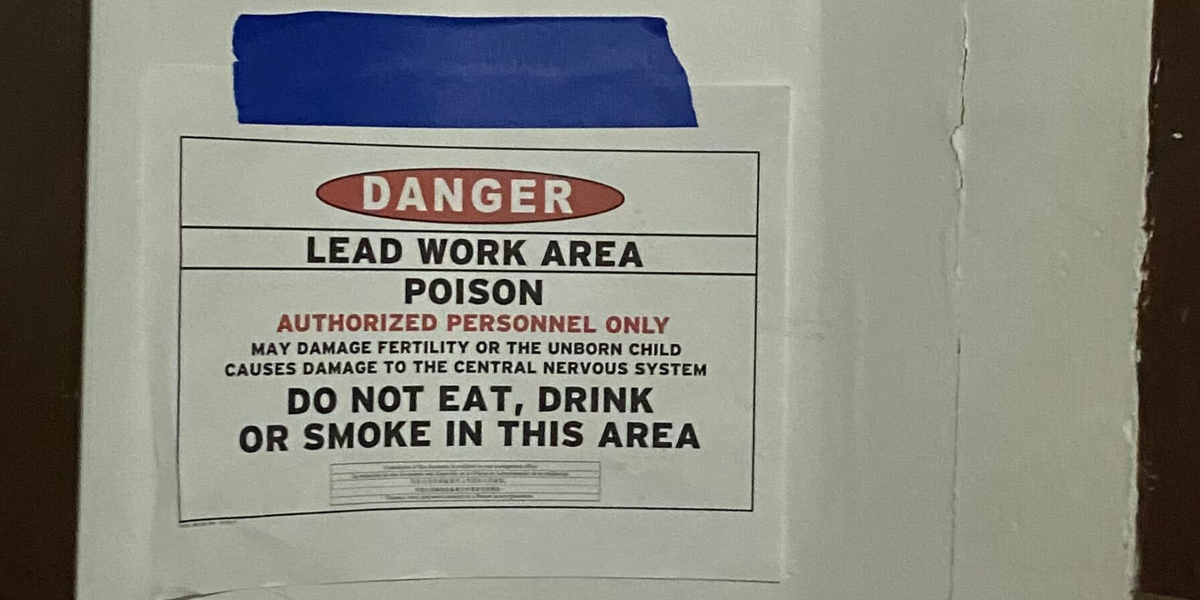

Deteriorating lead paint on a windowsill in Ingrid Rivas’ apartment in Mott Haven.

Jacyln Jeffrey-Wilensky

The Rivas’ landlord, Marat Leschinsky, bought the building in 2022, according to property records. He owns or co-owns five other buildings in Brooklyn and the Bronx, city data shows, though none as troubled as 540 Concord Ave.

In an interview with Gothamist, Leschinsky said the building was in terrible shape when he took it over. But he said he’d hired a lead remediation company that had already tackled many of the building’s 33 units.

“The building was just neglected by the previous owner,” he said. “We’re making progress but it takes time.” The building still has 59 open violations, including four for lead paint in the Rivas’ apartment.

New city laws that go into effect in June and September will strengthen enforcement of the inspection rules and force landlords to remove lead paint on windows and doors by 2027, regardless of whether tenants are moving out.

The new amendments are desperately needed, Chachere said. The 12,000 apartments identified by Gothamist, caught in a cycle of repeat lead violations, are among the most troubled. Housing department data shows that they’re often plagued by other problems, including pest infestations and utility shutoffs.

That was the case for the Rivas family. They also dealt with infestations of roaches and rodents, which chewed holes in their clothes and nested in their kitchen stove. The gas and electricity shut off often, Rivas said, forcing them to cook on a butane camp stove and store fresh food in their neighbor’s fridge.

“We’re having trouble reaching that last tranche of buildings that are continuing to expose children,” Chachere said. “That’s where we need to do more work.”

A law to get the lead out

In 1992, Cordell Cleare fled a fire in her Harlem apartment building with an 11-day-old baby in her arms. She and her young family would return soon after, but her apartment still needed repairs that would take nearly two years to fix. Other damage was irreparable: Cleare said her son, who was a toddler by then, was poisoned by lead paint dust that had been disturbed by the repairs.

“I didn’t even know there was still lead paint [in the apartment],” said Cleare, who’s now a state senator. “I felt inadequate, I felt uninformed, I even felt guilty in a lot of ways, even though none of that was valid.”

The experience changed her life. She became a tenant organizer, and then led the city’s Coalition to End Lead Poisoning. At the time, there were few legal protections for tenants from lead exposure. In 1997, she signed on as chief of staff to City Councilmember Bill Perkins of Harlem, who sponsored a suite of regulations — titled the New York City Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act — to protect other children from permanent neurological damage. She said it felt like the arc of her life coming full circle.

“If I didn’t know any better, I’d think somebody planned it,” Cleare said.

At a press conference in 2003, she called Bloomberg’s opposition to the legislation “a slap in the face to the children of New York City.”

Deteriorating paint on a kitchen cabinet in Dabeyva Lobo’s Sunset Park apartment where city inspectors found lead paint.

Jaclyn Jeffrey-Wilensky

In addition to the requirement that landlords get rid of lead paint on doors, windows and other high-impact areas by 2007, lawmakers also removed a number of other provisions at the Bloomberg administration’s request, Chachere said. Gone was a provision that landlords inspect building common areas, such as hallways and lobbies, and a provision that the city use its property records to track aging buildings and proactively inspect them for peeling paint.

The resulting legislation was a “compromise,” said Morri Markowitz, who directs the Lead Poisoning Prevention and Treatment Program at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx.

Bloomberg vetoed the watered-down version of the bill anyway. The City Council had to override his decision to ensure the legislation became law.

Loeser, Bloomberg’s spokesperson, said the mayor had been concerned that the law as a whole would increase housing costs and make landlords less likely to rent to families with small children. But Loeser said Bloomberg made sure to uphold the measure once it became law, citing an uptick in lead paint violations issued by the city after 2004.

“Even though we disagreed with the law, we stepped up enforcement considerably,” he said. Loeser didn’t answer questions about whether Bloomberg’s assessment of the law had changed in the intervening years, or whether Bloomberg thought the compromises he pushed for affected its effectiveness.

Generations of exposure

Dabeyva Lobo has called a three-story building in Sunset Park home for almost her entire life. She was raised in the apartment across the hall from the one she lives in now. Her sister married the boy who lived upstairs. Other tenants lived in the building for more than 40 years before passing away, she said.

“This whole building is like a family,” Lobo said, sitting on the sofa in her brightly lit, spotless living room. Framed family photos fill the coffee table. Large pop art prints of Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn cover the walls.

But it’s what’s behind them that has upended life for Lobo, her girlfriend and two small children, ages 2 and 8. When Gothamist visited, aging paint flaked and peeled from walls, window sills and door frames, and there was a gaping hole in the kitchen wall that was covered haphazardly with masking tape. Lead paint has been detected in the apartment at least 11 times over the last seven years, city records show.

That places Lobo’s home on the extreme end of apartments that have received repeated lead paint violations over multiple years. Units like hers made up less than 1% of the repeat offenders identified by Gothamist’s data analysis.

Dabeyva Lobo in her Sunset Park apartment.

Jaclyn Jeffrey-Wilensky

Lobo said her landlord Xiang Dong Yang had painted over some of the deteriorating paint after she filed complaints with the city and health inspectors visited. But much of that new paint is now also peeling, she said. Housing department records show there’s been regular lead abatement work on the building since 2017.

“They didn’t do proper work,” Lobo said. “It’s all cracking.”

Yang did not return Gothamist’s request for comment.

Lobo said she was never tested for lead paint exposure as a child while growing up in the building. So far, her girlfriend’s children haven’t tested positive for elevated blood lead levels. The couple keeps a punishing cleaning schedule to keep it that way. They wipe down baseboards, sweep and mop daily, Lobo said. And they make sure the children wash their hands after playing on the floor.

Lobo and her neighbors, some of whom also have peeling lead paint in their apartments, banded together to sue their landlord over a host of problems — including lead paint, mold, pests and faulty electrical work — in 2021.

The building has amassed so many lead paint citations and other violations that the housing department placed it in its Alternative Enforcement Program, which features frequent visits from city inspectors and empowers the city to make its own repairs on “severely distressed” buildings at the landlord’s expense.

Closing lead loopholes

Many of the provisions stripped from the original proposal for Local Law 1 have been added back in recent years. Starting in June, for example, landlords will be held accountable for lead paint dust in their buildings’ hallways, lobbies and other common areas. The city will also have to use violation data to do targeted inspections of known problem buildings.

Rivas’ landlord eventually patched over some of the peeling paint and removed the lead-painted kitchen cabinets wholesale, leaving behind a gaping stretch of bare wall. Other areas of the apartment went unabated, despite months of repeated calls and complaints, Rivas said.

The older children’s blood lead levels had returned to a normal range by January 2024, according to medical records, but the youngest child’s levels were still above the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s action level.

In the spring of 2024, Rivas and the four children moved to a city-funded shelter in Parkchester, about five miles from their apartment. It hurt to leave her home and neighbors behind, she said. But it was the only way to keep her children safe from the lead, rats and other health hazards in the apartment.

“I feel much better,” Rivas said.