The January-March Employment Boom Kills the June Rate Cut Forecast

Sixty-eight days.

That’s how much time is left until the conclusion of the Federal Open Market Committee in June at which the overwhelming majority of Wall Street economists think the Fed will announce an interest rate cut. Absent a huge and unexpected shock to the economy, Friday’s job report makes that highly unlikely.

The dream of a June rate cut is dead.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics said that employers added 303,000 workers to their payrolls in March, more than 100,000 above the consensus forecast for 200,000. The revisions to January and February added in another 22,000 jobs, bringing the jobs-above-expectation figure to 125,000.

To get a sense of the underlying trend in employment, we look to the three-month moving average. This jumped from 265,000 jobs to 276,000 after adding in the March gains and the revisions. If the payroll numbers had come in as expected, the average would have declined to 234,000. So, the moving average is 50,000 jobs or 18 percent higher than expected.

Core Private Sector Hiring Was Strong

Government payrolls rose by 71,000, which was higher than the average gain of 54,000 last month. Of these, 9,000 were in the federal government and 49,000 in state and local government. By historical standards, the government gains are a relatively high share of the total gains, at nearly one-quarter, indicating that government hiring is still a big factor in the economy and the tightness of the labor market.

Private sector demand for workers, however, remains very strong. The private sector added 232,000 jobs, beating expectations for 170,000 and the prior month’s 207,000. This is the largest increase since May of 2023 and well above the average of 183,000 in the decade or so before the pandemic struck.

We’ve been urged by some of our readers to look at the private sector excluding jobs considered “government adjacent” in health care and social assistance. The idea is that while these jobs are technically in the private sector, many of them are very heavily dependent on government spending rather than the strength of the private sector. So by excluding them, you get a better sense of what truly private sector demand for labor looks like.

In March, healthcare added 70,000 jobs, which was above the average over the past year of 60,000. Social assistance added 9,000, which was below the 22,000 average for the preceding year. When these are subtracted from the private sector gains, we get a gain of core private jobs of 144,000. That is a lot of core jobs.

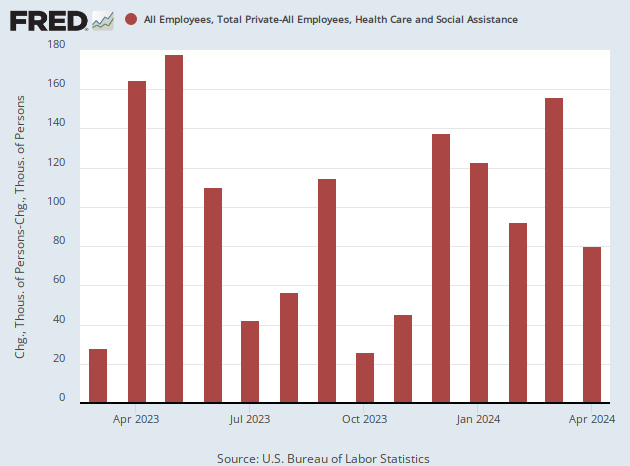

Note that this is a change from last year. For several months in 2023, core private sector jobs growth was anemic. The resilience of the labor market really was dependent on healthcare and social assistance. As the chart below shows, this really has not been the case since December of the last year. The rolling three-month average gain in core private sector employment is over 130,000.

The other thing to keep in mind when discounting employment gains for government and government-adjacent jobs is that while this might give a clearer picture of private sector labor demand, it can understate the economic impact of employment gains. Public sector and adjacent workers still get paychecks, buy homes, pay rents, shop for groceries, and otherwise add to consumer demand for the goods and services produced by the private sector. That’s one of the reasons that public sector jobs are likely to produce excess inflationary pressures: they’re adding to demand for private sector products but not producing them.

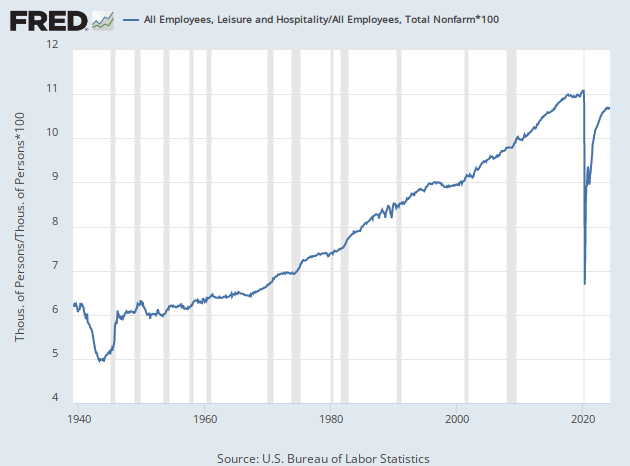

The hospitality and leisure sector added 49,000. Incredibly, it has taken until now for this sector to return to the pre-pandemic level of employment. Despite all the hiring in this sector, we’re now just 6,000 jobs ahead of the peak in February 2020. That’s a reminder of just how hard this part of the economy was hit by the pandemic lockdowns, social distancing, and remote work. As a percentage of the total workforce, leisure and hospitality is still below the prepandemic share and seems likely to stay below it going forward.

The Establishment Always Wins

Employment in the household survey lagged behind the gains in the establishment survey for months, leading some to conclude that the establishment survey was overstating the strength of the jobs market. In Thursday night’s Breitbart Business Digest, we argued that it was probably a mistake to read the data this way because the establishment survey’s estimates are derived from a larger sample size and appear to better fit the other economic data.

In the March jobs report, the discrepancy flipped. The household survey showed employment gains of 469,000, a bigger gain than the establishment survey. As a result, the gap between the surveys has narrowed. This is likely to continue to happen overtime as the household measure of employment catches up with the establishment measure.

The unemployment rate ticked down to 3.8 percent from 3.9 percent, defying predictions that it would continue to climb. This should dispel fears that unemployment would keep rising and maybe trigger the now legendary Sahm Rule recession marker. As a refresher, the Sahm Rule says that a recession is likely to be underway if the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate increases by half a percentage point or more relative to its low during the previous 12 months. We’re now just 30 basis points above the recent low.

The Time Limit for Data to Support a June Cut Has Expired

There are only two more jobs reports and more personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index reports between now and the June 11-12 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). It would take a very large, unexpected, and sudden change in direction to justify a cut based on anything coming out of those four reports after the three hotter-than-expected jobs reports and two hot PCE inflation reports we’ve had so far.

Fed officials appeared this week to be trying to move the market away from the expectation for a June cut.

- Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said that he expects one cut in the fourth quarter, which would mean in November or December.

- Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin said, “We have time for the clouds to clear before we beginning the process of toggling rates down.”

- Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashari said that he had forecast two rate cuts by the end of year but now thinks there may be no cuts. He even raised the possibility that the next move could be a hike.

- Dallas Fed President Lori Logan said on Friday, “I believe it’s much too soon to think about cutting interest rates.”

- Fed Governor Michelle Bowman warned against easing too early and also mentioned the possibility of a hike.

- Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester was surprisingly dovish in remarks to reporters on Tuesday, saying she still sees three rate cuts as likely appropriate this year. While she reiterated the official line of needing more data indicating softer inflation before a cut, she did add that “it’s a close call” on whether fewer than three cuts will be needed.

- San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said the three rate cuts are a reasonable expectation but added that because growth is “going strong” there is “really no urgency to adjust the rate.”

None of those comments sound like they’re coming from an official who thinks they’ll be ready to cut in 69 days.

The only truly dovish comments came from Chicago Fed President Austen Goolsbee, who brushed off the January and February inflation reports and continued to insist that the Fed could cut into strong growth and resilient labor demand without risking inflation. Goolsbee, however, is not a voting member of the FOMC this year.

In some appearances prior to Friday’s jobs report, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell stuck to the official line that the Fed needs to see clearer signs of lower inflation before cutting rates. He added, however, that it was too soon to say if the higher inflation numbers in January and February were “more than just a bump.”

While the jobs report had some indications of rising inflation—average hourly wage gains ticked up—it was not alarming in this regard. At the same time, it underscored the strength of the labor market that so many Fed officials see as providing an opportunity to wait and see what happens with inflation.

The market-implied odds of a Fed cut in June started the day near 60 percent. Following the report, the odds dropped below 50 percent. No doubt Wall Street’s economists will soon be pushing their forecasts out to July, where market odds now see a 70 percent chance of a cut. That’s 117 days from now.

We expect this will keep happening. The economy is approaching a rate cut like a ship moving toward the horizon. No matter how far we go, the horizon is always off in the distance, and the rate cut will aways be another 100 days away.